Amid all the recent furore over tax evasion or avoidance and the barely distinct line between them, I thought I’d throw my two penneth in, which of course I will fully declare to HMRC.

Let’s consider a new form of income tax. One that simplifies all twists, turns and nuances of the current system. A more straightforward tax that’s easier to assess, quicker to collect and almost completely unavoidable.

My proposal would be that everyone pays tax based their theoretical ability to earn.

HMRC could look at various parameters such as age and general health, but the most important of these would be your past employment history and your level of qualification. Both of these would of course be indicators of the kinds of salary you could command on the open employment market. We’d naturally have to assume the market was buoyant and that there would be an infinite number of suitable jobs available for every person able to take such a position. But as we all know, assumption is the lingua franca of the taxman

I’d propose that specialised analysts would set a tariff for each person, based on what they could earn in these idealised set of circumstances. This would effectively give a figure that each person should be paying, assuming they were working and in a job equivalent to their experience and education. Then HMRC could simply issue demands based on these notional figures. If, for example, you qualified as a teacher, you’d pay what a teacher should be earning. If you’d qualified as a solicitor or a doctor, you’d pay based on that ability to earn a salary consummate with your potential.

Now the controversial bit : My system would mean you’d pay these taxes regardless of if you were actually doing the job you were qualified for or not. If you trained as a brain surgeon, but decided that delving around in someone’s skull was no longer for you, no matter, you’d still pay the tax on a brain surgeon’s salary. Even if you went off to work as a shelf stacker in your local caring, sharing supermarket, you’d still be expected to pay the brain surgeon’s tax. Remember, your liability would be based on what you could be earning, rather than what you actually made. Likewise, if your only qualification was a silver swimming certificate but you somehow ended up as a city trader, you’d only pay tax based on your notional earnings potential, for example as a street cleaner or a career politician. On second thoughts, scratch the latter example as that screws with my argument.

Fair’s fair

I know that all sounds terribly unfair, but I’ve got that covered. Returning to my city trading, swimming certificate holder, he would have his potential earnings re-assessed every 5 years or so, and if it was shown that he could now command a higher salary, due to a newly gained experience at pushing buttons and answering phones on the trading floor, he’d have his taxation level increased, usually to that of the highest paid city trader in operation. He’d then pay tax at that level forever, even if he lost that fire in his belly and decided to pack it all in and wash cars for a living, he’d pay the tax of a top city boy. Moreover all this income flowing to the chancellor’s eager grasp would be adjusted annually by the rate of inflation, just to make sure they kept up with current standards of living. It’s only fair.

I know that all sounds terribly unfair, but I’ve got that covered. Returning to my city trading, swimming certificate holder, he would have his potential earnings re-assessed every 5 years or so, and if it was shown that he could now command a higher salary, due to a newly gained experience at pushing buttons and answering phones on the trading floor, he’d have his taxation level increased, usually to that of the highest paid city trader in operation. He’d then pay tax at that level forever, even if he lost that fire in his belly and decided to pack it all in and wash cars for a living, he’d pay the tax of a top city boy. Moreover all this income flowing to the chancellor’s eager grasp would be adjusted annually by the rate of inflation, just to make sure they kept up with current standards of living. It’s only fair.

You see, under my system there’d be no need to fill out complicated tax forms, no necessity for tax allowances or adjustments based on your true circumstances. Everyone would receive a tax demand calculated for them by HMRC and they’d have to pay it. No arguments. Even if you weren’t in work or you earned far less gross pay than the tax being demanded, you’d still have to find the money – Somehow. After all, you’d have the ability to be able to earn the going rate for a particular job, so why should the tax inspector have take into account what you actually earn. That demands far too much thought, effort and energy on behalf of busy government departments. If you earn less than what you’re qualified for then that’s your decision. Your problem. You still pay the tax.

Sound equitable to you? No, I thought not.

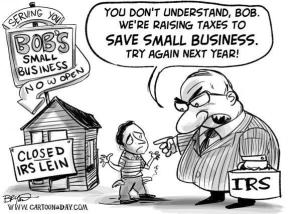

But then this, in case you haven’t already spotted my laboured attempt at a parallel, is exactly the way the current system of business rates works for retailers, and other businesses. It’s essentially a system of taxation based on a notional ability to earn money, regardless of the actual circumstances at the time or of our actual income.

The arguments for such a system as we were told last week on Radio 4 is that it’s easy to assess, easy to demand, and simple for businesses to pay. Brandon Lewis went to some length in his interview on the BBC’s Face The Facts programme to stress just how important he thought certainty was for businesses, even if that certainty is that you’re being mercilessly ripped off by a complacent under-informed government. To anyone outside the commercial property world, the idea that you’d pay a tax with no direct connection to actual revenue would seem ludicrous. Yet it’s something retailers face every month when they have to find the money to pay this fixed, non-negotiable charge, regardless of how much money they’ve taken in the preceding weeks. This ridiculous conceptual levy is now contributing to the fastest decline in the history of high street retail, yet it’s continuance is defended rigorously by ministers on a regular basis and apparently accepted as a reasonable proposition by the rest of us.

Our current system of business rates is a twisted perversion of what was originally a property tax intended to ensure local residents and businesses paid into local coffers for the provision of the local services they consume. Refuse removal, emergency services, council officers and the like. The simple idea being that the size of the property you occupied gave a rough guide to how much of these resources you’d call on in any given year. It was a bit of a blunt instrument but it was broadly fair and of course we all accepted it as a civic responsibility.

Community Chest

That really went out of the window when the current system of Uniform Business Rate or UBR was introduced in 1990. Under this system all businesses across the country paid into a central pot which was then shared out between local authorities across the country based on budget and need. This took into account that some areas may have a lower potential to earn rates from business which meant that more central government subsidies were required. Under UBR the richer areas would to some extent help support the poorer. A fair and equitable system, in theory, except that under UBR the rates you paid were now assessed on the value of your property, rather than it’s area. And there, hiding in the little detail of an adjustable annual multiplier linked to inflation, was the devil.

Now, instead of paying a proportion for your local facilities, you paid a property tax based on a deal you did with landlords on a commercial level, sometimes years in the past. You were no longer paying into a community chest for your local hospitals and lollipop ladies, you were paying a tax to central government. Not only that, it was a tax based on an assessment of the value of your property made by another, separate, government authority : The Valuation Office (VOA). They assessed the rough value of your property based on an aggregation of the local rental ‘tone’ and set a tariff on each property to which the annual multiplier would be applied. If this wasn’t complicated enough, the government then varied the annual multiplier based on a measure of inflation at an arbitrary point in the calendar, currently six months before any new charge would be due.

The principle of course was that deals agreed to acquire a property in any area would give a rough guide to the affluence of the local population and their likely spending, which in turn would give some indication of the potential turnover of the business paying the tax. A tenuous correlation at the best of times, one largely based on expectations and aspirations at a given moment. Even so this probably kept rough pace with reality during times of normal trading, although it was hardly the basis for a fair and equitable system of taxation. In fact it had more in common with more notorious historical levies such as the window tax or feudal tributes paid to Norman lords.

The principle of course was that deals agreed to acquire a property in any area would give a rough guide to the affluence of the local population and their likely spending, which in turn would give some indication of the potential turnover of the business paying the tax. A tenuous correlation at the best of times, one largely based on expectations and aspirations at a given moment. Even so this probably kept rough pace with reality during times of normal trading, although it was hardly the basis for a fair and equitable system of taxation. In fact it had more in common with more notorious historical levies such as the window tax or feudal tributes paid to Norman lords.

So, as with my mischievous suggestion in the opening paragraphs above, we have a system of taxation based on a theoretical assessment of earnings potential with no direct connection to ability to pay. The really odd thing is that we all seem to accept this as a fair arrangement. The various campaigns launched over recent years don’t seem to focus on the one salient point that for any tax to be fair it has to be related to actual earnings, not the murky notional musings of various self regulated government agencies.

The dictionary definition of a tax is : “a compulsory contribution to state revenue, levied by the government on workers’ income and business profits, or added to the cost of some goods, services, and transactions”. Perhaps this is why the government continues to call them business ‘rates’ ; Harking back to the original principles where your property was ‘rated’ in relation to it’s consumption of local resources. That’s plainly no longer the case, even more so now after recent revisions to rules that allow central government to hold on to a proportion of the rates collected by local councils paid into the central government pool.

Business rates are self evidently a tax in all but name, something we’re expected to overlook as an artefact of historical inertia and semantic subterfuge. After all, if it was correctly named, we’d all expect there to be some deference to the normal rules by which taxation operates.

Alternatives

Most proposed alternatives to business rates seem to be founded on tweaking what we have now. Base the annual multiplier on CPI rather than RPI has been the most popular to date, whilst the proposal to change to a land tax rather than a property tax has been around for a good while too. In fact Green Party MP, Caroline Lucas recently launched a Private Members Bill to that effect. There have also been a plethora of rebates and deferral schemes down the years for various business types or uplifts for others, none of which really fixes the inherent problems, especially for those businesses that don’t fulfil the very limited criteria.

One partial solution mooted several years ago was to carry out annual re-assessments using the £10M computer system developed by the government at the time, based on the principle of Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA). Although, like something from the Hitchhiker’s Guide the the Galaxy, that apparently now lies unused, gathering dust in the corner of a VOA broom cupboard, probably in a locked filing cabinet beneath a sign saying ‘Beware of the Tiger” .

The most likely shift that anyone has remotely expected from successive governments has been the shift from RPI to CPI, a principle that’s lately been applied to other government measures where it works to their advantage, most notably things like pensions . It’s also proposal was included as one of the recommendations in the Portas Review (recommendation 8) that the government has assured us all it’s ‘accepted’ it still seems a long way off. Yet more semantic tap dancing demonstrating that there’s a big difference between acceptance of an idea and actually doing anything about it.

Personally I think we’re well beyond the point where this would make any significant difference to the problem. In what is an inherently unfair system we appear to be focussing on degrees of unfairness, rather than pressing for a complete overhaul. To me that seems like playing into the governments hands. The difference is marginal. In January for example RPI stood at 3.3% while CPI was 2.7%. When and if ministers do finally bend and shift to CPI, are we really all going to breathe a collective sigh of relief over a difference of 0.6% in our annual rates bills?

Keep On Squeezing

None of these, with the possible exception of the land tax idea would re-establish the link between local service provision and the payment that was originally designed to cover the costs for these. Neither would any of them have any relationship with ability to pay, as with virtually every other fair system of regular taxation.

None of these, with the possible exception of the land tax idea would re-establish the link between local service provision and the payment that was originally designed to cover the costs for these. Neither would any of them have any relationship with ability to pay, as with virtually every other fair system of regular taxation.

We all seem to have blithely accepted a liability that has been foisted upon us all by a process of stealthy evolution from a simple local levy to a full-scale income tax. Collectively we hand over billions to the government on this basis, calmly and with little protest. The only reason we’re all getting out of our prams about it now is that falling commercial property values are no longer being reflected in this thoroughly disconnected system.

While property values remained flat or were adjusted in line with gradual increases in yield, UBR just about kept pace with turnover. But the commercial property boom of the past 15 years pushed retail rents beyond sensible sustainability, which in turn drove comparable increases in rateable values. The property crash of 2008 and the decline in consumer spending has now exposed the high water mark of unsustainable process. Yet ministers carry on sucking the reservoir dry, terrified of losing a guaranteed income and convinced that this creaky mechanism should lumber on regardless of imminent collapse.

But there are workable alternatives. Dr Adam Marshal from the BRC has advocated a local taxation regime based on profits, whilst I’ve long argued for a form of local purchase tax, similar to that in the USA. Perhaps, even more radically, we could combine it with VAT and add the charge at the till as they do over there. Then, not only would the burden of taxation be transparent to customers, it would show where a large proportion of the cost of operating a retail business lies. Something I’m sure many of us would welcome in the face of customer and landlord perceptions that we’re all amassing a personal fortune on a daily basis. Not only that, a direct link between the success of a local business and the income generated by local authorities would provide a sharper focus for councillors over issues that directly affect their performance, such as parking, local road infrastructure, planning, town management and the like. Given the fact that many retailers trade in areas where they don’t get a vote in local elections, a levy based on local performance would at least partly negate the frequently overlooked paradox of taxation without representation.

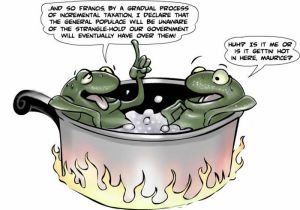

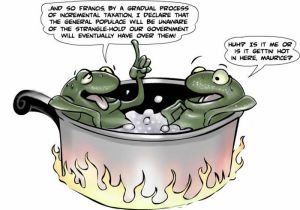

Boiling the Frog

Isn’t it about time we all called for a re-invention of the whole process of local business taxation? Rather than being complicit in the continuation of the status quo or accepting yet more bolt on revisions to a discredited process. Rather like the business rates system itself, we arrived at the position we’re in now by a series of incremental assumptions and expectations. It’s akin to the old adage of the boiled frog, and only now as we start to feel the heat are we beginning to sweat.

Personally I’m all for jumping out of the pot right now, rather than settling for a little more seasoning in the water I’m being cooked in.

also bricks and mortar operations who already pay a fair share of business rates. Their online sales may to a large extent be supporting other parts of their business. Taxing them more isn’t going to improve that situation. Increased taxation would also have to be passed on to customers, hence neatly strangling the golden goose that may be keeping many parts of the retail industry aloft.

also bricks and mortar operations who already pay a fair share of business rates. Their online sales may to a large extent be supporting other parts of their business. Taxing them more isn’t going to improve that situation. Increased taxation would also have to be passed on to customers, hence neatly strangling the golden goose that may be keeping many parts of the retail industry aloft.